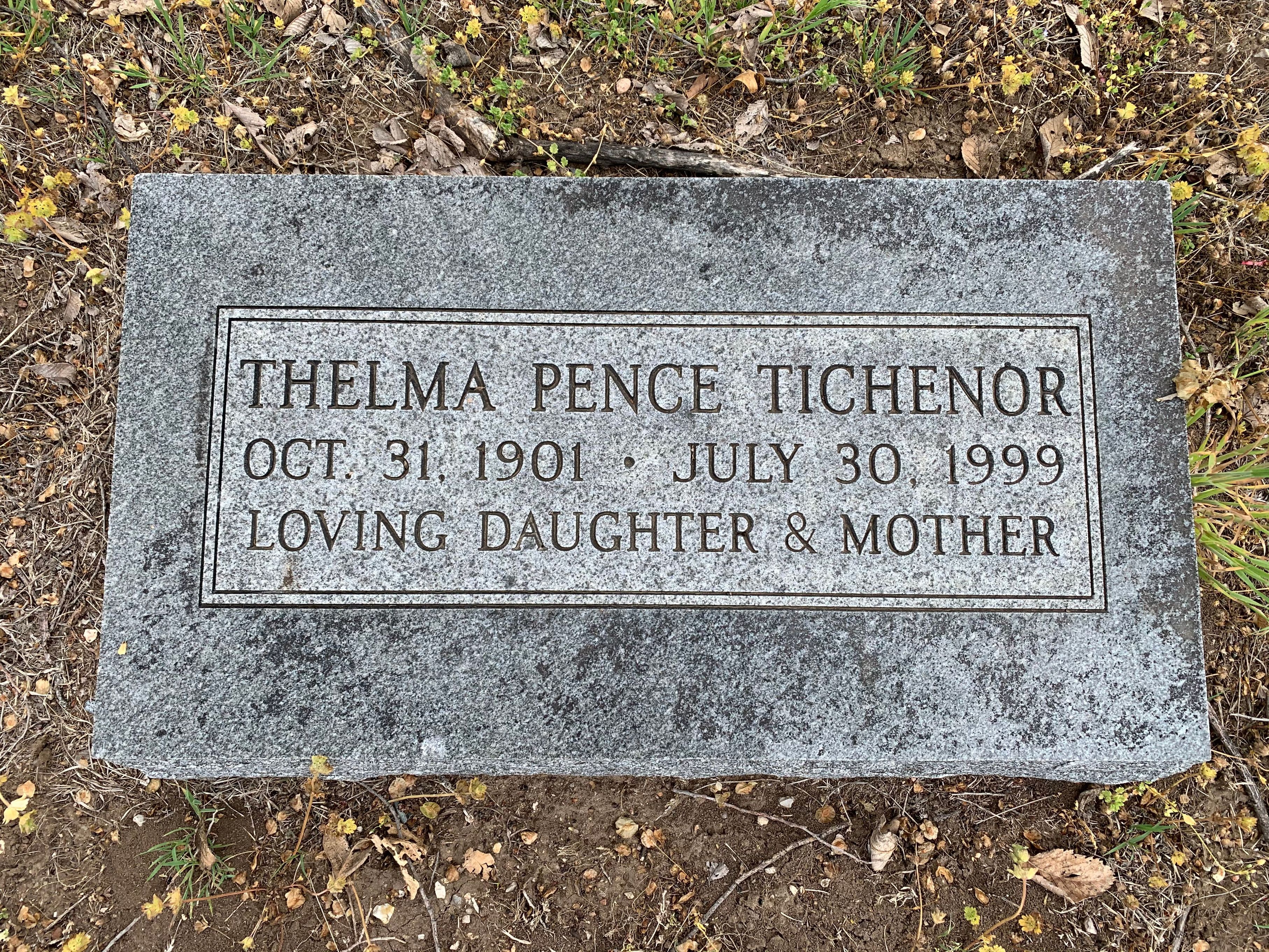

Name: Tichenor, Thelma Alicia(Pence)

Burial Date: 1999, 08/04

Age at Death: 97

Plot Location: 196 N

Notes: Divorced wife of George Humphrey, II

The following is entitled “A Short Memorial to My Mother, MRS. THELMA PENCE TICHENOR” October, 1901-July 30, 1999.

My mother had been in declining health in the spring and summer of this year, and died as a sequel to a fall she suffered in the early hours of July 28th. Her wishes had been for a traditional and very simple service here at the house. Fr. Tom Keith of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, Lyons, Kansas, was kind enough to conduct it.

The closed casket was at the north end of the living room, beneath a floral arrangement and in front of a large Chinese table upon which more flowers and an old photograph of her were placed. At the other end of the room were seated about thirty friends and relatives. It was much the same as it had been when her own parents died. I was fortunate to have the support of Max Moxley and Gordon Kling in helping to arrange matters.

The service started with a recording of Ave Maria. Part of the way through the service I was called upon to present a short eulogy. I managed that with some difficulty, then read Crossing the Bar. Gordon Kling sang the Welsh hymn All Through the Night, a cappella, and Fr. Keith concluded the service. A recording of Verdi’s Va Pensiero was played when it was time to rise and go. With the customary prayer at the graveside, all was concluded.

Several of those at the funeral asked me later if they could read the notes I had written about my mother. The difficulty there is that I had not spoken exactly to text and that my handwriting is hard to read.

I recalled that my cousin, Suzie Pierce Coxhead, prepared a nice memorial, with photographs, after her own mother died. I though it would be well for me to do the same especially since there are some relatives in California, as well as many friends and business associates of my mother who will miss her.

**************************************************************************

Remarks delivered at the funeral, Wednesday, August 4, 1999

My mother left the world on Friday, with almost as little trouble as on her arrival into it. She was born on the family farm two miles north of here (1 1/2 miles east on cemetery road from Sterling College corner and 1/2 mile north – house no longer there) on the afternoon of October 31, 1901. At the time, my grandmother was completely alone in the house, so that there was no one about to assist. My mother’s last two days were easy, and she was unconscious much of the time.

In her last three years, my mother suffered a number of small strokes and eventually became senile. Yet, she was always in good spirits and able to enjoy a rather restricted life in her own house, surrounded by her own things. Had she lived, she would have been wretched indeed, frightened and among strangers, confined to a bed in an institution.

At the end, her body was, as is said, no more than a cold, frail, husk, an image, made more telling by the sight of her physician’s little boy romping about in his father’s office, full of new life and energy, that same morning.

Yet that tired remnant had once given me life, love, and companionship and had returned much love and admiration to her own parents, for my mother was an attentive daughter and happy to be so. She could also show energy and resolution when required. Following a divorce at age fifty, she undertook a successful new career and carried on another forty years.

How my mother became a decorator is not much concern here, other than to say that Sterling College gave her a start. She taught Art and English in various Kansas schools and in Arizona. That, in turn enabled her to study in New York and in Paris, where she specialized in Interior Decoration. She was domestic by nature and had a good eye and an instinct for harmonious colors and compositions.

She first worked at Gump’s in San Francisco, then for a regular firm of decorators, Armstrong, Carter, and Kenyon, until I was born in 1935. Later, after seventeen years of marriage, she left me here in the care of my aunt, and returned to San Francisco, where Miss Kenyon of the old firm was good enough to get her established.

My mother’s passing leaves a wake of good, kind, friends of all backgrounds. She often said that he job enabled her to meet many interesting people who became friends and who have been friends to me also.

In temperament, my mother was much like her own father: independent-minded, quiet and sincere, whose character was like a newly minted gold piece, full weight, ringing true, with a soul that was pure and shining. A saying I shall always remember her by goes:

“Be Good, my son, and let who will be clever.”

I shall now read Crossing the Bar. It used to be found in many school texts, and my mother liked it.

*********************************************************

I will begin my additional remarks with an example that bears on her admonition. It illustrates how her conscience worked and guided her.

Some time in the late, late ’70s my mother got a call at home from Mrs. Kenyon’s old cook/housekeeper, :Velma,” who lived with her own mother, sister, and brother far out ‘on the avenues’ — southwest portion of the city. My mother had kept in touch with her, and at this time she was the lone survivor of her family. She told my mother that she needed half a pound of ground sirloin. Mr mother must have been concerned, for she asked me to buy some and take it out to her. That seemed a fool’s errand to me, and I was irked with my mother for promising it. Once I got there, tough, I suspected something might be wrong. Velma was sitting at the top of the steps, which had partially fallen in. The front door was wide open, and I could see all the way to the windows at the back. Poor Velma’s face was greyish, and she seemed slow. I left her the steak and a quart of milk.

When I told my mother about it, she called the police who, as it turned out, had her taken to the hospital. A few days later, my mother got a call from a social worker to say that Velma had died.

Had I followed my reason, I would never have gone out there, but my mother was the Good Samaritan and save me a large black mark on my page in the Lamb’s Book of Life.

Many of her friends have made the same points about her character when they have called me to send their condolences. She impressed them as being very forthright, without cuteness, affectation, or sentimentality; that she was interesting and the type of friend who lasts. She did not approve of yearning after frills or trying to satisfy appetites that were not important in “the grand scheme of things.” She hated brainless, Gadarene fashions in thought and behavior and she made a distinction between ‘fashion’ and ‘style’ about which she used to say, “never goes out of style.”

She was not religious, except in the most general sense, and did not cant about things. The title of William Allen White’s biography of (Calvin) Coolidge, A Puritan in Babylon, describes her well. They shared the values of a society from which both came.

My mother did have a sharp temper, not too easily raised but sometimes misdirected. He pet sin was probably wrath, though she did mellow as she became older and had other discomforts to occupy her. Her anger was generally triggered by behavior she found truly offensive: cruelty, cheating, predatory deception, or great selfishness. She was skeptical of moral arguments from intellectuals who can often think of good reasons to behave badly.

My mother had a strong sense of duty which may account for her fondness for veterans and military men she knew, particularly those that had been wounded or had been exposed to danger–people who also had an uncomplicated sense of duty and who did it.

She read occasional military biographies and memoirs of those who were able, colorful, or those she admired, such as Lord Nelson. I once took her to the Greenwich Naval Museum, where his uniform is displayed — almost the size of a boy’s. When she saw the hole in the shoulder from the musket ball that killed him at the moment of his great victory, she was quite overcome.

Probably my first memory of my mother is of a round, smiling face, framed in a copper-colored halo, looking down at me, talking, then turning and waving back at me from the door. I suppose that imprinted me or started me on my Oedipus complex –take your choice. I recall being seated at her side of a sofa, looking at a pack of Lucky Strikes in the old green wrapper. (My love for tobacco goes back a while.) I remember being seated on her lap in the car and I being fascinated by the bright, nickel emergency brake and the characteristic instrument panel of the Model A Ford. My grandfather, noting my attachment to my mother, joked to her that she would get to be extremely strong in a few years, carrying that calf around until he was grown.

I recall watching my mother writing letters and my trying to imitate the process with scribbles, or of being hypnotized as she made a sketch. They were always lifelike in a way I could never duplicate. Any drawing I make is too much thought-out and will, therefore, lack art school, she had been taught to do a “croquis” (sketch) of a face or figured in a very short length of time. This required an ability to see the essence of the subject in the mind’s eye and to make some quick, economical sweeps to get it down.

My mother put an artistic touch to the working space in her office. On the wall at the back or her desk, she affixed a few oddities, along with leaves and feathers that she had picked up from an interest in their shape, color and markings and also as mementos of the places where she’d found them. Any paper lying by her telephone was very quickly covered with doodles of geometric shapes, curlicues, abstract people, household items, etc. She produced this art-graffiti automatically, without much thought or effort.

My father had the same faculty with words as a result of his newspaper training. Having written to deadlines, he could tell a story clearly, concisely, and in an attractive manner. I remember that he would sit at a typewriter, stare at the paper, then rattle off several paragraphs at full speed. Unlike my mother, however, he thought more in abstractions and logical relationships. He always had an interest in literature, history, and science, and habitually carried a book about with him to fill in any idle time.

I inherited my mother’s ability to visualize things as well as her skill at handwork, which she expressed in embroidery and sewing. Some members of my father’s family are skilled also. His brother used to make violins. It was from my father that I came to have an analytical turn of mind and an interest in the reasons for things being as they are and why. It’s the source of an appetite for science.

My parents both sought to develop and encourage my nascent interests and abilities. My mother tended to buy me tools of different kinds. She once got me a little drawing board, T-square, triangles, French curve, compass, and ruler, all unbidden, in the course of a trip to an old art supply house on the edge of Union Square in New York. where she sometimes went to look at prints or to buy art supplies.

She may have imagined that I would become an architect, which was not far from the mark. I became a mechanical engineer. That made good use of the traits I inherited from both sides.

Although they had many differences and preferences that ultimately led to their parting, my parents saw to it that I enjoyed an excellent and rounded education. My father, in particular, supplied me with good books, scientific gadgets, radio supplies, etc. He bought me the microscope that I still use.

My mother used to take me back to Kansas each summer to visit her family and, once or twice, she went to on to San Francisco to do some work with her old firm. New York had cultural and business advantages of a high order, but that did not compensate for having to live a cramped life in a dirty, noisy, anthill. I will always recall how happy I was to be getting off the train at Newton to take the local up to Sterling. The evening breeze had a fresh, grassy smell of home. Correspondingly, when we left in the Fall, it was to return to the belly of the beast.

I saw my mother a number of times in high school, college, and after I went out in the world. Each time she was more prosperous, always happy, and much given to various enthusiasms, some of which I confess I found hard to share.

When she was starting her business in the ’50s and ’60s, San Francisco was still a pleasant, interesting place, without much crime or crowding, where one could easily live and work. She shared a downtown office with another decorator friend and was able to run her errands, visit the antique shops, fabric houses and workshops easily on foot or by bus.

Though my aunt learned to drive, my mother never did. It wasn’t in her nature. To get around that problem, my mother enlisted a number of companionable friends as assistants. Ben Liebert, Gertrude Colomb, Jeanette Hoover, Jane Wallace, and Sharon Daugherty, and probably others I’ve forgotten, all afforded my mother mobility and hours of good company and so deserve gold stars and a special mention.

Another pleasant aspect of San Francisco around Union Square at that time was, as she would say, “This is like a town, not a city. You’re always running into people you know.” That was true. The better stores, restaurants, hotels, professional offices, banks, and corporate headquarters were all in a rather confined area. And, if you walked to Market Street and looked south you would see the green hills of Twin Peaks. My mother circulated easily and quietly in that milieu in tailored tweeds, a conventional hat, and a shopping bag of fabrics and samples, as inconspicuous as a mallard hen.

Also, in those early years, her uncle and aunt, Jack and Myrtle Gash, were alive and kept a nice, hospitable home in Berkley, close by their two children, Betty Pierce and Bob Gash, with their own pleasant households. Most of that happy clan is gone or scattered, but while they were all there my mother had the feeling that she was not too far from her family. She also had her brother Arden, in Davis; as well as another aunt, Mable, and her daughter, Kathleen, in the East Bay.

In the ’60s my mother moved into a very nice little apartment with a separate entrance, located in a sunny place that overlooked the Marina, the Bay, a bit of the bridge and the Marin headlands. It was a building owned by friends in what was then still a family neighborhood. The bus downtown stopped at the end of the block. Over the years she made a very pretty and harmonious place for herself that she enjoyed for more than thirty years.

From this point my mother began to live a little more freely. She took trips to the British Isles, then later to France, Russia, and even China, all without much trepidation.

Her politics also changed. She had been a New Deal Democrat, but she was offended by the war, the lying, the vulgarity, and the sentimentality of Johnson, and by what followed. Finally, having put some together, she found herself being robbed through taxes and inflation.

In 1972, I reappeared on her doorstep with some ideas — a computer program for simulating a neutral network among them — but without a clear idea of whether or how to pursue them. At any rate, the cowbird check was welcomed back into the nest. It did not turn out to be such a bad thing. I made myself useful for the moment by typing her bills and estimates and running errands. Through one of her clients, Frank Williams, I also got a job teaching math and statistics at San Francisco State College(as it was then). It paid well (on an hourly basis). and provided nice perquisites: access to their computer system, office space, a swimming pool, and a good library. Cousin Suzie Coxhead, ever obliging, sold me her Ford Mustang. This gave me more mobility and also meant that I could do some of my mother’s driving and more pickup and delivery chores for her. I saved rent living with her, and she could use her time to more advantage.

Things went well until, in the fall of ’76, my mother got a call from a friend in Sterling relating that my aunt seemed to have suffered a stroke that left her ambulatory, but alone in the house and perhaps confused.

My mother put her projects on hold and flew back to Kansas. She straightened out the situation, got a girl from the college to stay in the house as a roomer in case anything happened, and returned after a few weeks.

I stayed with my aunt over the Christmas vacation. She had another stroke, but recovered, I think, by the time I left. However, there was another incident in the spring, and my mother had to leave once again until my classes were over.

My poor mother was facing a nasty situation. Her business had been humming along, she was enjoying life and able to turn out a good quantity of valuable work. But here she was, called away from all that to nurse my aunt and at a great disadvantage. She could not drive, could not lift my aunt, could not deal with many of the things required to keep a strange house running. Add to that the fact that my aunt was often uncooperative or hostile toward her sister and not grateful for her attention.

The frustration and worry of the situation should have driven my mother to tears, had she been the type. But she kept at it until she could get back to the work she found so rewarding.

I returned at the start of the summer. My aunt had always been very kind to me, and I got along well with her. I was also able to take care of some urgent house repairs. This started a pattern that continued for years and turned out well in a number of ways, though it kept me nailed to a teaching job I was then considering leaving. I was able to keep Auntie functioning most of the time and in her own home with the help of Mrs. Clydia Renollet and Mrs. Dora Blue to look after her. Dora finally had to live with her full time while I was away.

My aunt was due this attention. She had looked after me and after her own invalid mother. But, in 1987, when Mrs. Blue’s husband died and she moved to another town, there was no choice but to put Auntie in the local nursing home. I was planning on carrying on in the old way in my vacations, but she broke a hip and died of the complications.

My mother and I came out at Thanksgiving to attend the funeral. From that time until she moved her, she would return with me every summer and liked it.

My mother had also fallen and broken a hip in San Francisco. Later, she fell here in sterling and broke both wrists. In all of this there was never a complaint. She was stoic and took things in stride.

Life in San Francisco became more and more difficult and irritating by degrees, even for a younger person. She could no longer manage the busses as she had done, and the trip downtown took twice as long. Street people slept in the entrance of her office building. Her office was twice robbed, and she had two friends who were murdered in the time she lived there.

In the early ’90s my mother gave up her little office, with some sadness I suspect. She did conduct a little business with her old clients from her desk at home. Her regular associates and I drove her around as required.

There were other unnerving incidents in San Francisco. The earthquake flattened several buildings down the hill from us and was frightening while it was taking place. Then, in 1992, after the Rodney King verdict, I found myself locked in the middle of a traffic jam in front of City Hall, surrounded by a sea of rabble (to use the accurate term) that was flowing down toward Market Street. It was alarming to feel so helpless there without a cop in sight. The police were pursuing some ‘non-provocation’ policy of keeping hidden which was maintained that evening.

I went to a luncheon the next day at the St. Francis Hotel. I saw a number of stores downtown that had windows broken and had been looted of merchandise. Broken glass was everywhere, even from some of the shops facing the street on the ground floor of the hotel itself, right on Union Square.

I was glad to retire from teaching about that time. An interesting thing was that I succeeded in getting my network program to work on my own little PC. It was descended from the one I had tried to develop on the college main frame twenty years before and which then was a black hole for gobbling up machine time. Coincidentally, I had been given a little engineering design project to execute. It turned out to be the only piece of work I ever did to go into production.

It made no sense to stay bottled up in San Francisco, given this place in Sterling. So without fuss, she sold some things, gave away others, and arranged to ship the remaining ones. After 44 years she had no regrets, only great satisfaction, repeating a remark attributed to Clark Gable, she often said, “I was lucky and I know it.”

She had a better life here in many ways. It was quiet, safe and without strife. She had a comfortable chair by the large window in the den where she could enjoy the birds and squirrels, flowers for the picking and various vegetables in season.

She also got more exercise here in a large house with stair to climb and more space to move around in. Often I would also walk her around town or to the college and back. She had no trouble meeting people; there were so many that had known my aunt and some whom I knew. She got much pleasure from the company of Marjorie Miller, Max Moxley, and Dr. Dysart, with occasional visits from Polly Collins, the daughter of a lifelong friend with whom she had taught school in Lindsborg.

There were also visits from good friends from San Francisco, and even one from Bob Gash’s daughter, Mary Lynn Franzia, and her daughter, Carol. Her brother, Arden stopped here, as did Betty Pierce’s son, Allen, at the beginning of this summer. And, along with the telephone, there were no feelings of being cut off or lonely.

In the spring of ’96 my mother had to undergo major surgery. She appeared to recover fairly well, but had a couple of small strokes, one of which put her in the hospital overnight and impaired her memory.

These steps downward would be followed by partial recovery. Then there would be another sudden loss, and so on. She came to lose her sense of equilibrium, her ability to write, and her short term memory. It even became difficult to get her to take solid food, But fortunately, through all her trials her disposition did not change, nor did she become depressed in any way. She accepted everything that happened to her, and her attitude to death seemed to be one of indifference, but that is probably the way it is with the veery old. However, if she were in a situation where I was concerned for her, as when she had her surgery, she could read my long face and would give me a wink and a smile.

Even on the Wednesday evening before she died, while she was still partially conscious, I bent across the bed to give her a kiss and a squeeze of the hand. She returned the squeeze weakly and made an attempt at a wink. As is turned out, that was good-bye.

It was when I started making funeral arrangements and looked back that I realized I had spent 27 years with my mother. And yet, it seemed no time at all. It was odd, but companionable and interesting. Our roles reversed, especially towards the end, when I became the parent and she the affectionate, good-natured child she had once been. There is no rational basis for it, yet when she died it was as if the gold rivet had fallen out of my life. It will be some time before the pieces come together again in another way.

This memorial may read too much like hagiography. I don’t think that my mother would have approve of that herself, yet she led a good life and was “an original.” I owe it to her as a token of gratitude, and I do know also that her memory and example will afford some pleasure and interest to her friends.

8888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Thelma Alicia Pence Tichenor

| Birth | 3

Sterling, Rice County, Kansas, USA

|

|---|---|

| Death | 30 Jul 1999 (aged 97)

Sterling, Rice County, Kansas, USA

|

| Burial |

Sterling, Rice County, Kansas, USA |

| Plot | 196 N |

| Birth: Oct. 21, 1901 Sterling Rice County Kansas, USA |

|

| Death: | Jul. 30, 1999 Sterling Rice County Kansas, USA |

age 97, divorced wife of George Humphrey, IIFamily links: Spouse: George Humphrey Tichenor, II (1906 – 1959) Children: |

|

| Burial: Sterling Cemetery Sterling Rice County Kansas, USA Plot: 196 N |

|

| Edit Virtual Cemetery info [?] | |

| Created by: Lawcas Record added: Apr 26, 2013 Find A Grave Memorial# 109538592 |

|